By Jesse Robitaille

This is the second story in a three-part series exploring the state-of-the-art forensic technology used by the expert committee of the Vincent Graves Greene Philatelic Research Foundation.

Relatively unassuming in appearance, the VSC6000 packs a powerful punch when it comes to philatelic expertization.

Its high-resolution colour camera, zoom lenses and various light sources and filters – from ultraviolet (UV) to visible and infrared wavelengths – give the user an unparalleled power to see a stamp’s invisible features.

“You get very consistent lighting in a dark environment, and it gives absolutely constant readings,” said Garfield Portch, president and chair of the Vincent Graves Greene Philatelic Research Foundation.

“That’s what you spend the $100,000 for,” he added, referencing the unit purchased by the Toronto-based Greene Foundation in 2012.

Manufactured by Foster + Freeman in the United Kingdom, the original VSC unit was launched in 1979. Since then, the company has produced several updated versions, the latest of which – the VSC8000 – was released in 2015.

The Greene Foundation is one of only a handful of philatelic organizations in the world to own a VSC6000. Its expert committee uses the powerful unit to fulfill part of the foundation’s mandate, which includes expertizing the stamps and postal history of Canada and British North America.

No longer a “touchy-feely” process, philatelic expertizing has flourished with the help of forensic analysis, said Portch, who’s a long-time member of the Greene Foundation’s expert committee.

With up to 160-times magnification, the VSC6000 produces images with a minimum of 24,000 pixels per inch and a whopping 18.5 megabytes in size.

“They’re huge images, which is absolutely wonderful for inspection,” he added.

But it’s not just size that matters; the VSC6000 can detect a variety of inks, microtype and latent images, among other features found on stamps.

Microtype (centre) and latent images, including the numeral ‘8’ (bottom) hidden on the $8 grizzly bear stamp issued in 1997, are uncovered by the VSC6000.

A WORLD UNCOVERED

Using the long-running high-value “Canadian Wildlife” series, which began in 1997, Portch provided several examples of just what the VSC6000 can uncover.

Upon the release of the series’ first stamp, design manager Georges de Passillé was quoted in Canada Post’s Details magazine as saying the Crown corporation “had taken every possible step to keep it from being an easy target for fraud.”

These measures included steel engraving, which was used as it’s “difficult to replicate the texture and exquisite detail you get from the thick ink and from the paper being pressed into engraved lines during intaglio printing,” Passillé said.

On the $8 grizzly bear stamp (Scott #1694) issued in 1997, a latent “8” appears on the bear’s back right leg using “a device called a latent-image finder,” Portch said.

“It’s a beautiful piece of engraving, and the machine will automatically bring it up for you.”

Another security feature added by the stamp’s engraver Jorge Peral includes tiny images of bears used to make the grass and sky.

While those features were both highlighted in Details, another one – this unannounced by Canada Post – was uncovered by the VSC6000. Two lines below the word “CANADA” in the stamp’s top-right corner consist of microtype with the words “MAIL” and “POSTE” repeated (and with the latter word italicized).

In addition to reading microtype printed with either lithography or intaglio, the VSC6000 can measure distances to the hundredth of a millimetre.

In 1998, the series’ second and third stamps – a $1 loon (SC #1687) and $2 polar bear (SC #1690) – were issued. Years later, using the VSC6000 to look at the latter stamp, Portch saw “all these holes shot through.”

“Originally, I thought those holes were just lousy printing, but they are too constant to be lousy printing. They’re actually a security feature,” he said. “If you do a colour reproduction of the stamp using a laser printer, all those holes fill in, so if you get one of those and the holes are filled in, you know you’ve got yourself a forgery.”

These halftone dots interwoven into the clouds are made from tiny images of a polar bear paw, which were also “printed underneath the intaglio, in spot-colour offset inks,” according to an email sent to Greene Foundation expert Charles Verge by the stamp’s designer Steven Slipp.

Three more security features – halftone dot loon eggs on the stamp featuring that animal plus microtype on both issues – were also found by the foundation’s experts.

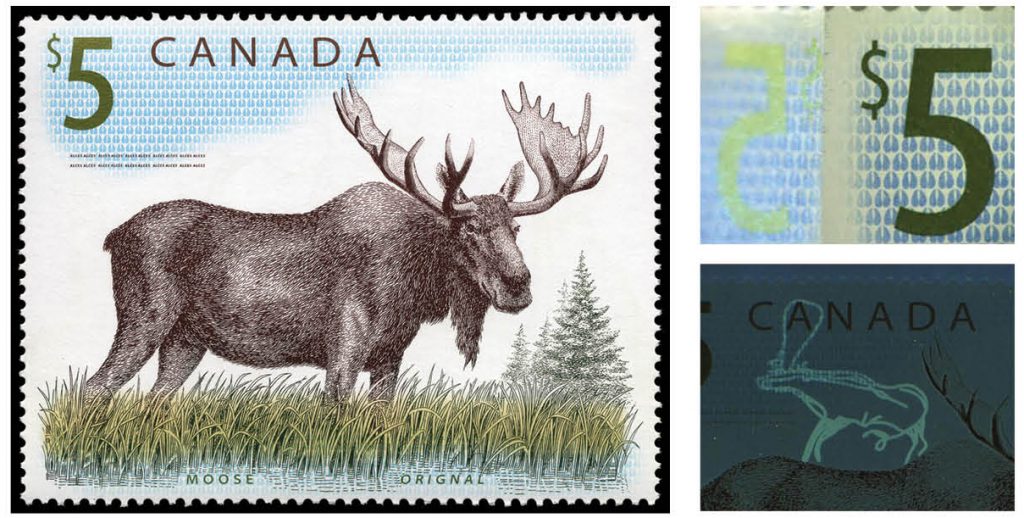

On the series’ next issue, a $5 moose stamp (SC #1693) released in 2003, there’s “a nice big security marker,” Portch said.

“It’s a hieroglyphic moose done with a fluorescent ink. It’s pretty cool to be able to spot that stuff now,” he added, about the Mi‘kmaq petroglyph that was printed in varnish ink and glows under UV light.

Similar to the loon and polar bear stamps, the moose issue uses tiny images of a moose’s hoof in halftone dots to create the sky, and microtype is included below the “$5” denomination.

Not announced by Canada Post, however, were another two security features, including a microtype copyright mark showing the year 1999 (another attempt to thwart would-be counterfeiters, who might automatically use the 2003 issue date).

Lastly, printed using optically variable ink (OVI), the stamp’s denomination is a difficult-to-reproduce metallic green colour.

With the VSC6000, the foundation’s experts can detect OVI using floodlighting, magnification and a mirror to change the viewing angle.

“This is a really cool process,” said Portch. “OVI is a Swiss invention designed for painting cars, but the Brits decided they could use it with the ‘Castles’ issue in 1988.”

The high-value “Castles” series, which included four issues from 1988-97, needed to be redone because Xerox had recently introduced a coloured photocopier that made reproducing the original issue easy.

“Great Britain found a lot of the mail leaving the country to certain destinations were carrying photocopied stamps,” said Portch, who added OVI “can’t be photocopied.”

“You’ll find the OVI on the $5 moose and $10 blue whale, but I think you’ll see it as a security feature in a lot of future stamps, too.”

The series final story will look at Canada’s $10 blue whale stamp, the country’s largest and highest-denominated issue, under the light of the VSC6000.