By Jesse Robitaille

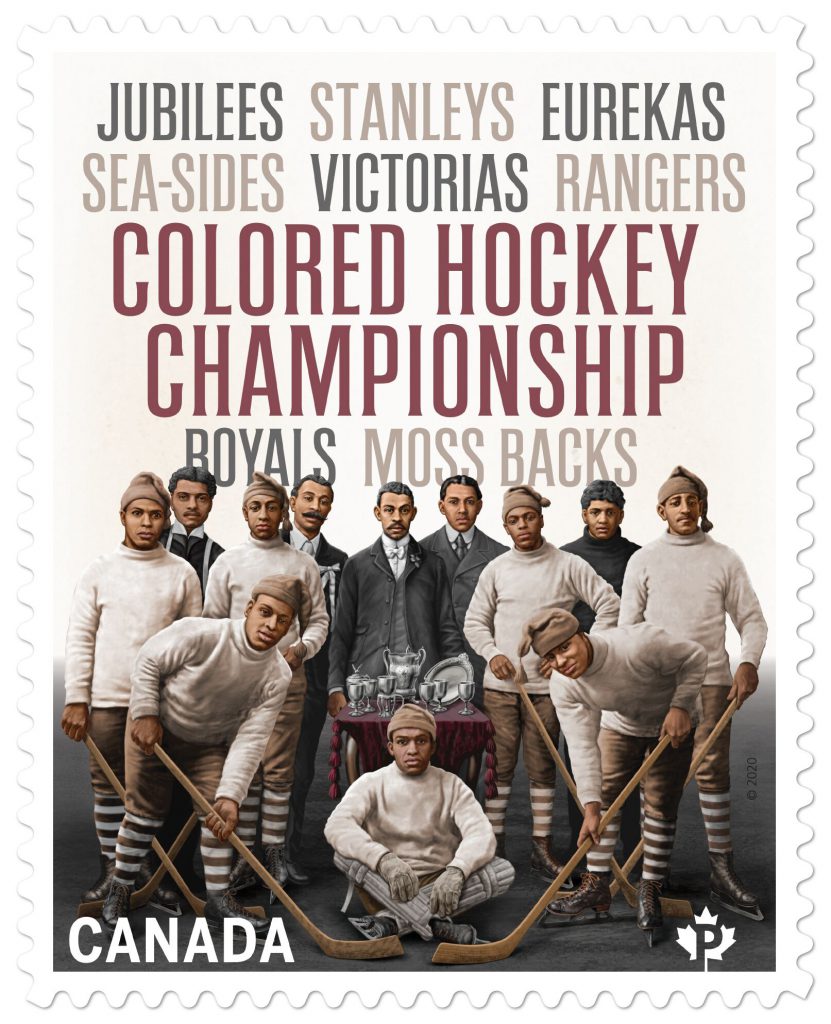

Not outright offensive but lacking a true understanding of Canadian history, Canada’s recent Black History Month stamp is making me think.

I guess that’s the point: the postal service – in this case, “Canada’s storyteller” – highlights a topic, and we all think about it. We learn about the issue and discuss it, and together we move forward.

At least that’s the idea.

The Colored Hockey Championship stamp – while celebrating black accomplishments – highlights Canada’s general ignorance about the darker aspects of its history.

(It’s similar to Canada’s inability to come to terms with its treatment of Indigenous communities despite all the talk of “truth and reconciliation.” Earlier this year, RCMP officers considered shooting Indigenous land defenders at the blockade of the Coastal Gaslink Pipeline on Wet’suwet’en territory in British Columbia. As I write this on Feb. 7, police have since removed the blockade, arrested protestors and set up a four-kilometre checkpoint that excludes everyone other than Coastal GasLink workers—even media isn’t allowed to cover what’s happening).

Don’t get me wrong; I like the stamp, but Canada Post’s promotion of it – in Details magazine, on its website and in its press release – skirts Canada’s history with racial segregation, which is the real story here.

I’ve thought about it all week, and I now believe Canada Post should’ve taken a different angle. After all, it’s Canada Post’s role – at least in part – to tell Canada’s story.

After going back and looking at the Crown corporation’s promotion of the stamp, I agree with one west-coast mayor who says there’s a “strong colonial slant to it.”

Is Canada’s less-than-stellar history with blacks being “whitewashed,” as Toni Boot, the mayor of Summerland, B.C., suggests?

She recently took to her personal Facebook page to protest how the story of the Colored Hockey League is told through the recent issue.

“I know it is Black History Month. But, really? Commemorating segregation? And ‘Colored’? Not only is it spelled the American way, but colored is a colonial/Jim Crow (southern U.S.) word,” wrote Boot on Feb. 3.

“Why doesn’t Canada Post instead commemorate abolishing slavery in Canada?”

I’ll admit, at first I disagreed.

While segregation isn’t the scope of the stamp, it does highlight the league’s role in overcoming it, I thought. It even showcases some groundbreaking hockey history (the slapshot and butterfly goaltending style – now indispensable parts of the game – were both used for the first time by players in this league).

Boot and I had a bit of a back and forth, and she explained further.

“Segregation and racism and the related struggles should be the scope of the stamp! Canada Post ‘whitewashes’ its meaning on their website.”

At first, I didn’t consider how segregation – and Canada’s history with it – should be the focus of the stamp. I initially told her the stamp “shines a light on our history without revision,” but upon returning to Canada Post’s website, I’ve had a change of thought.

“Celebrate Black History Month with this booklet of 10 Permanent domestic rate stamps recognizing an important time in Canadian ice hockey history,” reads the website.

“More than just incredible athletes, these players made important contributions to Canada’s national sport with their fast-paced, physical games and their down-to-the-ice style of goaltending. Today we celebrate their achievements.”

Boot said spoke with someone at Canada Post on Feb. 7, about a week after she made her original Facebook post, and explained how this focus on hockey – rather than black struggles amid racism and segregation – is misguided.

Later that day, she did the same with me.

“It wasn’t the stamp itself that really was my concern,” Boot told me. “It was the lack of context – or background, or history – that’s on the Canada Post website. It speaks to the Colored Hockey League’s contributions to Canada’s national sport, which is an achievement – it’s admirable – but what it doesn’t speak to, of course, is the segregation and racism that’s behind it. Or the struggles, which continue today. We don’t have segregation in Canada any longer, but there’s definitely still racism, and we’ve seen it in the sport of hockey very recently. It still exists.”

It happens beyond the game of hockey, too.

In 2014, while Boot was running for city council – four years before she was elected as mayor – the sign at her business, Grasslands Nursery, was defaced with racist and sexist slurs.

(She didn’t mention this to me; I was doing some digging and came across the story myself.)

This racism, which has persisted throughout Canada’s history, extends to pre-Confederation, when slavery was legal in the British colonies comprising present-day Canada.

With all its ugly warts, racism is part of Canada’s history. While most British colonies, including Canada, abolished slavery in 1834, segregation persisted well into the 20th century. This included segregation in schooling, health care, housing, employment and commercial establishments—even cemeteries.

“While the stamp is great, and it is something worthy of being recognized as part of Black History Month, it doesn’t tell the story,” Boot told me. “It’s like a glossy book cover without going inside and seeing what it’s all about.”

And therein lies modern Canada, a country that “insists on being surprised by its own racism,” as black activist and author Desmond Cole told Macleans magazine this February.

A prime minister seemingly survives a blackface scandal, and Chinese Canadians are taking the blame for the spread of coronavirus—maybe there’s more here than meets the eye.

Boot’s goal with protesting the stamp’s promotion was to start a conversation, which “could be the best thing that comes out of it,” she told me.

“You know what social media can be like, but I’ve had great conversations with media like CBC and yourself, and Canada Post earlier today, and that’s great. I know it’s difficult if you’re not part of this group. Your perspective is different, and that’s the important piece – to look at things with a bigger perspective.”