Historically a positive affair worthy of the exclamation, “Happy Canada Day,” this year’s 154th anniversary has taken on a more serious tone, with some calling for the celebration to be cancelled altogether.

The latest outcry came in late June as hundreds of Indigenous children’s remains were found in unmarked graves near three former residential “schools” in British Columbia, Saskatchewan and Manitoba. In May, the remains of 215 children were found buried near the Kamloops Indian Residential School in British Columbia. The following month, another 104 potential graves were uncovered at the Brandon Indian Residential School in Manitoba. Just a week before Canada Day, on June 25, upwards of 751 unmarked graves were found near the Marieval Indian Residential School in Saskatchewan.

“This was a crime against humanity, an assault on a First Nation people,” Chief Bobby Cameron, of the Federation of Sovereign Indigenous Nations, Saskatchewan’s provincial federation of Indigenous groups, told the New York Times after the sombre discovery.

Over more than a century, through funding from the Canadian government’s Department of Indian Affairs, about 150,000 Indigenous children were placed – some of them by force – in residential “schools” administered by Christian churches across the country. Their stated aim was “to educate and convert Indigenous youth and to assimilate them into Canadian society,” according to the Canadian Encyclopedia, which added more than 130 residential “schools” operated in Canada between 1831 and 1996. Their operational peak came in 1931, when more than 80 of the “schools” were open across the country.

According to Justice Murray Sinclair, the chair of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), the children were widely abused and entirely prohibited from speaking their languages. Thousands of the children disappeared, with death estimates ranging from 3,200 to more than 30,000, in what the TRC called “cultural genocide.”

CANADA DAY DEBATE

With these preliminary findings at residential “schools” – more are expected as other locations are searched – today’s holiday has become the focus of widespread debate among Canadians and within Indigenous communities.

While some people are calling for the holiday’s cancellation, others believe it should go ahead as planned (or with more Indigenous representation), and some activists are proposing Canada Day should be declared a national day of mourning.

Several “tweets” from various sources are shared below, offering a snapshot of people’s comments about what today means to the country, the land and the people who live here leading up to July 1.

We’ll continue to be there for the people of Cowessess First Nation and for Indigenous peoples across the country – and we’re committed to working together in true partnership to right these historic wrongs and advance reconciliation in concrete, meaningful, and lasting ways.

— Justin Trudeau (@JustinTrudeau) June 24, 2021

“The hurt and the trauma that you feel is Canada’s responsibility to bear,” Prime Minister Justin Trudeau said in a media statement last week, “and the government will continue to provide Indigenous communities across the country with the funding and resources they need to bring these terrible wrongs to light.”

He later reiterated on Twitter: “We’re committed to working together in true partnership to right these historic wrongs and advance reconciliation in concrete, meaningful, and lasting ways.”

Earlier this week, Trudeau also told reporters it’s “important” that Pope Francis “makes an apology to Indigenous Canadians on Canadian soil,” referencing the churches’ roles in running the “schools.”

Federal officials have announced the country’s official Canada Day event, to be held virtually, will feature Indigenous representation “as an important moment for dialogue and conversation,” Heritage Minister Steven Guilbeault is quoted as saying in a June 29 CTV News report.

“We are featuring Indigenous artists and musicians in ways we’ve never seen before for a Canada Day event,” he added, telling reporters individual communities can choose to cancel fireworks or other events on Canada Day.

182 more found in B.C.

Don't cancel Canada Day. Make it a day of mourning. https://t.co/uc0YPjDprE

— Fatima Syed (@fatimabsyed) June 30, 2021

In the days leading up to Canada Day, another 182 human remains were found in unmarked graves near St. Eugene’s Mission Residential School (now the luxury St. Eugene Resort) in Cranbrook, B.C.

Soon after, reporter Fatima Syed, the vice-president of the Canadian Association of Journalists, called for Canada Day to be “a day of mourning” rather than cancelling it.

The response from within Indigenous communities is similarly divided. More than 1.67 million people self-identified as Indigenous in the 2016 census, and Canada’s more than 630 First Nation communities represent more than 50 Nations and 50 Indigenous languages, according to a recent federal government report.

The Oshkaatisak Council of the Nishnawbe Aski Nation (NAN), which represents dozens of First Nations in northern Ontario, is not acknowledging Canada Day, according to a June 29 statement. Instead, NAN is encouraging people to “wear orange and spread awareness about the shameful history of Indian Residential Schools and the devastating legacy that continues today.”

“The Government of Canada also knew, and they are finally acknowledging it. As a nation of Indigenous Peoples, we must stand strong and shout this out to the rest of Canada. This country’s true history is finally being revealed, and it’s time to stand together and demand justice and accountability.”

Indigenous novelist David A. Robertson, a Governor General Award winner, also encouraged people to “wear an orange shirt not a maple leaf” in a June 27 Twitter post calling for Canada Day’s cancellation.

“It’s a day where we can mobilize to figure out how we can make this country one that is worth celebrating,” he added.

So again: for at least this year, #CancelCanadaDay. Wear an orange shirt not a maple leaf. Honour survivors and children who did not survive, and stand in solidarity with Indigenous people. /5

— David A. Robertson (@DaveAlexRoberts) June 27, 2021

Other people, including Parry Stelter – a “Sixties Scoop” survivor originally from Alexander First Nation-Treaty Six Territory in Edmonton, Alta. – don’t want to see Canada Day cancelled.

“We should be standing at attention,” he told CBC News for a June 26 report, “… but standing at attention in fully acknowledging the full history of Canada and all its atrocities and the genocide and the residential schools.”

Stelter, the president and founder of Word of Hope Ministries, added: “The fact of the matter is that we still all live here. And so we have to make the most of it and move forward and not just be resilient and not just survive, but learn how to thrive in our lives. But I totally understand if my people or anybody else don’t want to celebrate. I totally understand because we all grieve in different ways.”

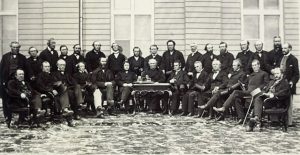

A photograph by James Ashfield captures Canadian artist Robert Harris’ 1884 painting, Conference at Québec in 1864, to settle the basics of a union of the British North American Provinces. It was later destroyed in the 1916 Parliament Buildings fire. Photo by Library and Archives Canada, C-001855.

OTD: CONFEDERATION

On today’s date in 1867, the British North American colonies of New Brunswick, Nova Scotia and the Province of Canada, the latter of which became Ontario and Québec, were proclaimed as the Dominion of Canada. The move came about four months after Parliament passed the British North America Act, which later became the Constitution Act and laid the foundation for the fledgling dominion.

“In most parts of the new Dominion, it was a dazzling sunny day. The reverberation of a brass band could be heard in many towns,” according to Canada: A People’s History, a 17-episode documentary series published by CBC.

“In Toronto, children were given Union Jacks to wave and an ox was roasted in front of St. Lawrence Hall, with the meat then distributed to the poor. In Ottawa, a military review on Parliament Hill fired a salute. The soldiers forgot to take the ramrods out of their rifles and the iron rods arched over Sparks Street. In Quebec City, a cannon was fired on the Plains of Abraham to mark the day and most Canadiens spent the time by the water, happy to have a long weekend.”

John A. Macdonald was appointed as Canada’s first prime minister by Charles Stanley Monck, 4th Viscount Monck, who served as the country’s first Governor-General following Confederation.

Macdonald’s wife Agnes, who he married earlier that year on Feb. 16, marked the momentous occasion in her diary.

“This new Dominion of ours came noisily into existence on the 1st, and the very newspapers look hot and tired, with the weight of Announcements and Cabinet lists,” she wrote. “Here – in this house – the atmosphere is so awfully political that sometimes I think the very flies hold Parliaments on the kitchen Tablecloths.”

The delegates of the Québec Conference meet in October 1864. Photo by Library and Archives Canada, C-006350.

CHARLOTTETOWN, QUÉBEC CONFERENCES

Confederation was the product of a pair of conferences held in 1864 in Prince Edward Island and Lower Canada (present-day Québec), which together with Upper Canada (present-day Ontario) was part of the Province of Canada.

In September 1864, Prince Edward Island – then a British colony – hosted the Charlottetown Conference. Originally slated to discuss the union of colonies in the Atlantic region, delegates from New Brunswick, Nova Scotia and Prince Edward Island were “persuaded by a contingent from the Province of Canada, who were not originally on the guest list, to work toward the union of all the British North American colonies,” according to the Canadian Encyclopedia. P.E.I. officials found the terms of union unfavourable and refused to join, choosing instead to remain a colony of the British Empire.

The following month, delegates from five British North American colonies – the Province of Canada, New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island, Nova Scotia and Newfoundland – gathered in Lower Canada for further discussions about uniting as a country. After adjourning on Oct. 27, the delegates drafted the “72 Resolutions,” most of which was produced by Macdonald, a lawyer with both legal and constitutional experience.

“As it is, I have no help,” Macdonald reportedly told his friend and fellow lawyer Sir James Gowan, who he later appointed as a senator. “Not one man of the conference (except Galt in financial matters) has the slightest idea of constitution making. Whatever is good or ill in the Constitution is mine.”

Macdonald was referring to Alexander Galt, another Father of Confederation who proposed several financial resolutions, including how the colonies’ existing debts would be shared and managed.

Altogether, the Québec Conference welcomed 33 delegates plus two observers, including:

- George Brown;

- Alexander Campbell;

- George-Étienne Cartier;

- Jean-Charles Chapais;

- James Cockburn;

- Alexander Galt;

- Hector-Louis Langevin;

- John A. Macdonald;

- William McDougall;

- Thomas D’Arcy McGee;

- Oliver Mowat;

- Étienne-Paschal Taché;

- Edward Barron;

- Chandler Charles Fisher;

- John Hamilton Gray;

- John Mercer;

- Johnson Peter Mitchell;

- William Steeves;

- Samuel Leonard Tilley;

- Adams George Archibald;

- Robert Dickey;

- William Alexander Henry;

- Jonathan McCully;

- Charles Tupper;

- John William Ritchie;

- Joseph Howe;

- George Coles;

- John Hamilton Gray;

- Thomas Heath Haviland;

- Andrew Archibald Macdonald;

- Edward Palmer;

- William Henry Pope;

- Edward Whelan;

- Frederick Carter, who was an observer; and

- Ambrose Shea, who was also an observer.

A third conference was held in London, England, in December 1866, when 16 delegates from the Province of Canada, Nova Scotia and New Brunswick met with British officials to draft the British North America Act.

MORE COLONIES JOIN CONFEDERATION

A six-cent stamp issued in 1970 by Canada’s Post Office Department marks the centennial of Manitoba joining Confederation.

Three years after Confederation in 1867, another two areas joined Canada.

On July 15, 1870, the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) transferred control of Rupert’s Land and the North-Western Territory to the Canadian government.

Comprising a third of present-day Canada, Rupert’s Land served as the HBC’s exclusive commercial domain from 1670-1870.

Named for its location in relation to Rupert’s Land, the North-Western Territory included present-day Yukon; mainland Northwest Territories; northwestern mainland Nunavut; northwestern Saskatchewan; northern Alberta; and northern British Columbia.

Most of these areas were formed into a new territory called the Northwest Territories; however, a region near Fort Garry – an HBC trading post seized a year earlier by Louis Riel and his Métis followers during the Red River Rebellion – was established as the province of Manitoba by the Manitoba Act.

A six-cent stamp also issued in 1970 marks the centennial of the Northwest Territories’ entry into Confederation.

B.C. & P.E.I. JOIN CONFEDERATION

On July 20, 1871, British Columbia became Canada’s sixth province; however, this outcome was of no certainty throughout the preceding decade, during which time residents of the colony debated joining their U.S. trading partners or upholding colonial power.

At the same time, Prince Edward Island was also exploring its options, which included becoming its own dominion or joining the United States. The colony began building a railway while starting early negotiations with the United States in 1871, but two years later Macdonald – always a critic of U.S. expansionism – negotiated to have Prince Edward Island join Canada as the country’s seventh province.

The federal government assumed the colony’s extensive railway debt, and Prince Edward Island entered Confederation on July 1, 1873.

The 100th anniversary of British Columbia’s entry into Confederation is celebrated on a seven-cent stamp in 1971.

NEARING & INTO THE 20TH CENTURY

On June 13, 1898, the Yukon was formed from part of the Northwest Territories following a boost in population during the Klondike Gold Rush a year earlier.

Seven years later, on Sept. 1, 1905, Saskatchewan and Alberta were also formed out of part of the Northwest Territories.

Nearly half a century passed before another province joined Canada.

The centennial of Prince Edward Island’s entry into Confederation is commemorated on an eight-cent stamp issued in 1973.

On March 31, 1949, Newfoundland became the country’s 10th province following years of debate about the self-governance of what was then a British dominion (not unlike Canada).

The following day, on April 1, prime minister Louis St. Laurent made the first ceremonial cut into the only blank stone plaque remaining over the entrance to the Peace Tower in Ottawa. The plaque was one of 10 erected in 1920 amid the reconstruction of the Parliament Buildings following a fire during the First World War.

“We are all Canadians now,” said Newfoundlander F. Gordon Bradley, who accompanied St. Laurent at the ceremony more than seven decades ago.

The Post Office Department issued a 17-cent stamp featuring Yukon’s provincial flag as part of its 1979 ‘Canada Day’ series.

NUNAVUT CREATED IN 1999

Finally, on April 1, 1999, Nunavut was created from part of the Northwest Territories.

Beginning in the late 1960s and continuing through the 1970s, a sustained effort took hold among Inuit groups to negotiate land claims with the federal government and secure their own territory.

Negotiations intensified in the 1980s and ultimately led to the July 1993 Nunavut Land Claims Agreement Act between the federal government and Government of the Northwest Territories, which laid the foundation for the creation of the territory of Nunavut on April 1, 1999.

The 50th anniversaries of the establishment of Alberta and Saskatchewan are marked on a five-cent stamp issued in 1955.

The creation of Nunavut was the first major change to Canada’s map since Newfoundland and Labrador joined Confederation in 1949, and it arose from the largest Indigenous land-claim settlement in Canadian history.

The new territory encompasses about one-fifth of Canada’s total landmass and is home to fewer than 40,000 people, most of them Inuit.

Nunavut means “our land” in the Inuit language of Inuktitut.

1927 CONFEDERATION STAMPS

In 1927, Canada’s Post Office Department (known as Canada Post since 1981) issued a colourful set of stamps marking the 60th anniversary of Confederation.

It was the first issue following the “Admiral” series (Scott #104-34), which ran from 1911-28.

On June 29, 1927, eight stamps were issued—five commemoratives in the “Confederation” issue (SC #141-45) and three in the “Historical” issue (SC #146-48).

The first issue, an orange one-cent stamp (SC #141), depicts Macdonald, who was Canada’s second longest-serving prime minister. With two non-consecutive terms, he served for nearly 19 years altogether.

A 17-cent featuring Newfoundland’s provincial flag was also issued as part of the 1979 ‘Canada Day’ series.

FATHERS OF CONFEDERATION

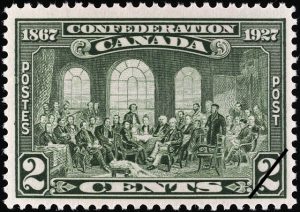

The second issue (SC #142) was a green two-cent stamp depicting the Fathers of Confederation based on an oil painting by Group of Seven artist Robert Harris.

The painting was also used as the focal point of a 1917 three-cent Confederation stamp.

The third issue (SC #143), a brown-carmine three-cent stamp, depicts the Parliament Buildings in Ottawa. Situated on Parliament Hill, Parliament’s Centre Block overlooks the Ottawa River. The building contains the House of Commons, the Senate and the parliamentary offices.

The Peace Tower, which dominates the central axis of Centre Block, contains the Memorial Chamber in remembrance of Canada’s fallen soldiers. At the rear of the building is the Parliamentary Library.

The fourth stamp, a violet five-cent issue (SC #144), shows Sir Wilfrid Laurier, Canada’s seventh prime minister and the first French-Canadian prime minister (1896-1911).

Born in 1841 in the village of St. Lin, Qué., Laurier entered Parliament in 1874. Three years later, he became a member of the Dominion cabinet before eventually becoming prime minister in 1896.

In 1897, Queen Victoria knighted Laurier while he was attending ceremonies in connection with the Diamond Jubilee of the Queen’s accession to the throne. He died during the winter of 1919 and was buried in Notre Dame Cemetery, Ottawa.

The series’ fifth issue, a dark blue 12-cent stamp (SC #145), depicts a map of Canada in 1867 and 1927 with light blue shading symbolizing the country’s coast-to-coast expansion.

A one-cent orange stamp featuring first prime minister John A. Macdonald belongs to a 1927 set marking Canada’s 60th anniversary.

TRUTH & RECONCILIATION

“There is systemic racism in Canada,” Prime Minister Justin Trudeau said at a press conference last June, after half a dozen Indigenous people were shot by police in two months.

“It means that Indigenous peoples, Black Canadians and racialized Canadians are far more likely to suffer violence at the hands of the authorities and police than non-racialized Canadians.”

A 2017 study by CBC, which assembled the first country-wide database of every person who died or was killed during a police intervention, found a steady increase in deaths from 2000-17. More than 70 per cent of victims suffered from mental health and substance abuse problems, and Indigenous and Black people were disproportionately overrepresented.

“For example, black people in Toronto made up on average 8.3 per cent of the population during the 17-year window, but represent nearly 37 per cent of the victims. In Winnipeg, Indigenous people represent on average 10.6 per cent of the population, but account for nearly two thirds of victims.”

The ‘Fathers of Confederation’ grace a two-cent green stamp issued as part of the 1927 ‘Diamond Jubilee’ issue.

These cases are just the latest iterations of Canada’s long history with racism, which dates back to pre-Confederation.

“Infamously, the British North America Act only mentions, ‘Indians and lands reserved for the Indians’ in a single sub-clause, assigning responsibility for both to the federal government,” wrote Brian Gettler, assistant professor of history at the University of Toronto, in a three-part essay published in 2017.

“The ‘Fathers of Confederation’ first adopted the phrase without debate at the Quebec Conference in 1864, adding ‘Indians’ to the federal powers proposed by the Canadian Liberal-Conservatives in their aborted 1858 project of British North American Union, while replacing the less specific ‘Indian territories’ with ‘lands reserved for Indians.’ Along with the Indian Department and Indigenous policy more generally, this sub-clause remained absent from parliamentary debate on both sides of the Atlantic in the years following 1864 and from the London Conference that in the winter of 1866-67 produced the final version of the BNA Act.”

Historians have “long replicated this silence, finding no role for relations with Indigenous peoples in the constitutional origins of modern Canada,” added Gettler.

“Historians of Indigenous-state relations have concurred, unanimously downplaying Confederation while instead focusing on changing legislation from 1850, the 1860 shift in responsibility for the Indian Department from the empire to the colony, Canada’s 1869 purchase of Rupert’s Land from the Hudson’s Bay Company, the Red River Resistance, and the numbered treaties of the 1870s. Though correct to concentrate on these critical issues, we need to do more; we need to place them at the heart of our understanding of state formation and changing political thought in the mid-nineteenth century. This is critical if we are to avoid replicating the ‘Fathers” imperial and imperious perspective that, though consciously centred on land, resources, and the liberal individual, declared relations with Indigenous peoples a mere political afterthought.”

In his 2008 book, A Fair Country, John Ralston Saul explores three myths of Canada’s foundation, arguing the famed “peace, order and good government,” which supposedly defines the country, is a distortion of its true nature. He notes every foundational document drafted before the British North America Act used the phrase, “peace, welfare and good government.”

A 12-cent dark blue stamp depicting the country’s borders in 1867 and 1927, when the issue was released, rounds out the Confederation set.

“Saul’s story begins – as every sensible essay on the Canadian identity must – with the fur trade, specifically with the economic and domestic relationships that were established between Europeans and Natives over the first 250 years of settler life in Canada,” reads an April 2009 review by the Literary Review of Canada. “As Saul points out, more often than not it was the Natives who were teaching and helping the newcomers survive, and in marrying Native women most European men were marrying up—greatly improving their social, political and economic lot in life. These relationships were partnerships in every meaningful way, and through this constant intermingling the Métis character of the Canadian people was shaped.”

Saul expands on this theory in two ways, the article adds.

“First, he emphasizes the oft-ignored role of the Natives as full partners in the military, civil and commercial affairs of the Canadas for the first 250 years of their existence. Since then, though, we have been engaged in what he calls ‘a double denial’: a denial of our own history, along with a denial that aboriginals even exist in a way that matters to our own flourishing as a country.”