By Chris Hargreaves

In 1913, Lord Northcliffe, the owner of the British Daily Mail newspaper, offered a £10,000 prize for the first flight across the Atlantic Ocean, but there were no attempts before the outbreak of the First World War.

When the “Great War” ended in 1918, Northcliffe again offered a £10,000 prize, which was equivalent to about $650,000 in today’s money after accounting for inflation and currency devaluation throughout the last 100 years. Given the technical advances made in aviation during the war, a number of aircraft manufactures actively competed for the prize.

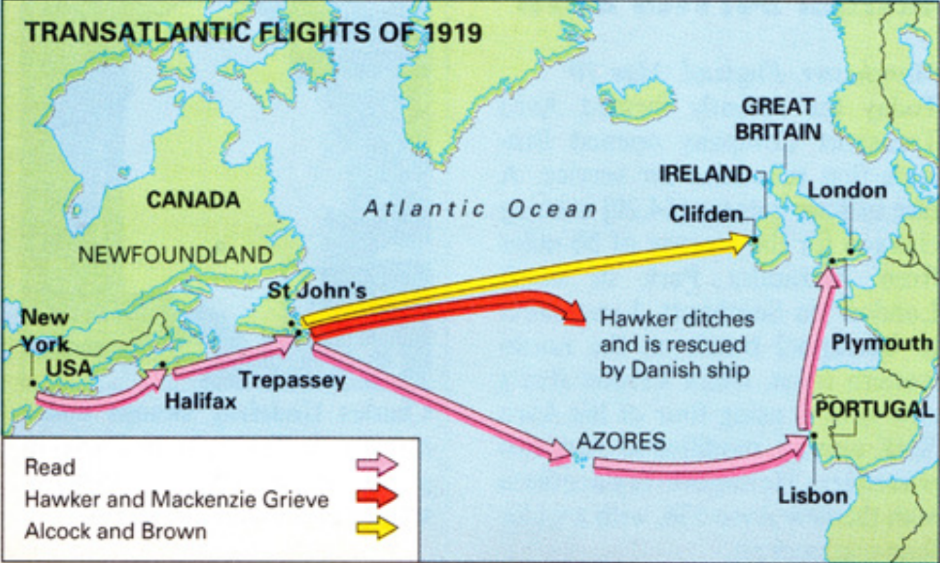

The conditions of the competition required the flight to be made by a single, heavier-than-air machine between any point in Great Britain and any point in Canada, Newfoundland or the U.S., and it had to be completed within 72 hours.

Then a colony, Newfoundland was the starting point for most of the attempts as it’s the closest part of North America to Europe; however, the capital St. John’s is still about 3,200 kilometres from the Irish coast.

HAWKER & GRIEVE

The first aviators to arrive in Newfoundland were Harry Hawker, pilot, and Lieutenant-commander Mackenzie Grieve, navigator.

Their aircraft, the Sopwith Atlantic, was a modified version of the Sopwith B-1 bomber developed during the war. It was powered by a single 350-horsepower Rolls-Royce engine and had a cruising speed of nearly 170 km/h.

The aircraft arrived by steamer before being assembled in Newfoundland and test-flown on April 11 and 12.

Hawker and Grieve were then ready to attempt flying the Atlantic but had to wait for suitable weather—both to take off from the small airstrip available and to cross the ocean itself.

RAYNHAM & MORGAN

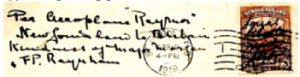

While they were waiting, Major Frederick Raynham, pilot, and Major C. W. F. Morgan, navigator, arrived with the Martinsyde Raymor.

This aircraft was specially produced for the trans-Atlantic competition by Martinsyde Ltd., which was Britain’s third largest aircraft manufacturer during the First World War. The aircraft was based on the Martinsyde Buzzard, a long-range escort fighter that entered production in 1918, just as the war was ending.

The Raymor was a standard biplane, but the crew were placed far back to allow a large fuel tank to be mounted in the middle of the fuselage – near the centre of lift – so as fuel was used, the decrease in weight did not alter the trim and handling of the aircraft. The Raymor was powered by a 285-horsepower Rolls-Royce Falcon engine and had a cruising speed of 161 km/h. It was quickly assembled and test-flown on April 18.

Raynham and Morgan also began waiting for suitable weather to attempt a trans-Atlantic flight.

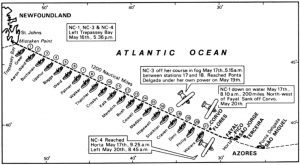

The U.S. Navy planned a flight across the Atlantic using three NC-4 ‘flying boats,’ each of which carried a crew of six.

U.S. NAVY

Meanwhile, the U.S. Navy was also planning a trans-Atlantic flight.

The navy didn’t have the equipment to compete for Lord Northcliffe’s prize but was interested in the prestige and publicity that would come from being the first to fly the Atlantic. It planned a flight across the Atlantic by three Navy-Curtiss (NC) “flying boats,” which were developed for long-range anti-submarine patrols.

These were large aircraft: their wingspan of nearly 40 metres was larger than that of the much-later Boeing 727.

They were powered by four 400-horsepower Liberty engines and carried a crew of six.

The C-5, a hydrogen-inflated ‘blimp’ developed for patrols during the war, is shown alongside its ground crew in 1919.

The three flying boats were to fly from the U.S. via Canada, Newfoundland, the Azores and Portugal to England. This meant the longest leg of the flight – from Newfoundland to the Azores – was about 2,250 kilometres. To support the flight, a network of destroyers was stationed at 80-kilometre intervals across the Atlantic to help with navigation and provide assistance in the event of problems.

The NC-1 and NC-3 arrived in Trepassey, Nfld., on May 10. They attempted to leave for the Azores on May 15 but were overloaded with fuel and could not get off the water.

The NC-4 was delayed by engine problems and did not arrive in Trepassey until May 15.

While extensive preparations were made for the NC’s flight, the U.S. Navy’s “balloonists” were also keen to show what they could do. They proposed a direct flight across the Atlantic by the C-5, one of the hydrogen-inflated C-class “blimps” developed for patrol duty during the war.

Their plan was approved by the U.S. Navy Department but kept quiet as it was uncertain whether modifications to the C-5 would give it the range to cross the Atlantic. The final decision would be made after the C-5’s positioning flight from Montauk Point, N.Y., to St. John’s, Nfld., where it arrived at 11 a.m. on May 15.

The flight to St. John’s was a great success: the airship was airborne for 25 hours and 50 minutes and travelled 1,894 kilometres but only used 750 of its 1,900 litres of fuel.

But as a storm rolled in while the C-5 was being serviced – with gusts of wind up to 100 km/h – the aircraft broke loose from its moorings and was blown out to sea.

The NC-1, NC-3, and NC-4 set off for the Azores on the evening of May 16 while Hawker and Grieve, as well as Raynham and Morgan, were waiting for the gale that destroyed the C-5 airship to clear so they could attempt a direct flight by the more northern route.

The NCs began by flying in formation along the line of destroyers, but after a while, the navigation lights on the NC-3 failed so the aircraft parted ways to avoid the risk of a collision.

The flying boats flew at 136 km/h, so they could pass a destroyer every 40 minutes or so. As they passed the first destroyer, the Greer, news of their progress was passed down the line. When the news reached Commander Raymond Spruance on the Aaron Ward at Station 2, “Spruance told the officer of the deck to put the ship on course and the Aaron Ward was swung around to a heading that pointed her bows toward the Buchanan, 50 miles away on Station 3.”

“Flood lights were turned on the eight-foot-tall numeral ‘2’ on the Aaron Ward’s fantail, while on the bridge the quartermaster of the watch switched on the ship’s searchlight and turned its milky beam into the wind. The officer of the deck told the gunnery officer to begin the firing of starshells from the ship’s 3-inch gun. As the starshells burst at 10,000 feet, the Atlantic was bathed in the ghostly white light of their burning mag- nesium. When the NCs radioed the Aaron Ward that her pyrotechnics were seen, the firing of starshells was secured and all eyes on board scanned the northwest. A few minutes later the dim lights of the aircraft were spotted: and then the three flying boats roared by, the sounds of their engines almost drowned out by Aaron Ward’s whistle and siren. Spruance had his radio officer notify the Buchanan that the NCs had passed and were on their way, and on board the Buchanan all hands jumped to their stations to repeat the Aaron Ward’s evolutions.”

The system of navigation by destroyer worked well at first, but in the morning, the aircraft ran into thick fog, heavy rain squalls and high winds.

The NC-1 became lost and could not contact any ships by radio. The captain decided to touch down on the water until he could establish his position, but the aircraft landed badly in the heavy swell and high waves, and part of its tail was carried away. After five hours of bailing to try and keep the hull afloat, a Greek ship, the Ionia, appeared out of the fog and rescued the crew.

The NC-3 also became lost, and its captain, Commander John Towers, made a similar decision to land on the Atlantic. The flying boat hit the crest of a wave as it was landing and was badly damaged. The crew could hear the destroyers on the radio, but could not contact them: the ships were searching for the aircraft to the west of the island of Flores, but the NC-3 was south of it. Towers decided to taxi toward the islands while a crewman hung onto the tip of the starboard wing to keep the port wing out of the water by providing a counterbalance. They reached the harbour of Ponte Delgada after two and a half days on the water.

The NC-4 also lost contact with the destroyers but reached Horta in the Azores on May 17 at 11:23 a.m. (local time)—five minutes before Horta was enveloped in fog.

MEANWHILE, ACROSS THE POND…

Back in St. John’s, the weather was improving on the morning of May 18, and it was also reportedly clearing over the Atlantic.

Hawker and Grieve, as well as Raynham and Morgan, quickly set about preparing to fly with the hopes they would still be able to reach England before the Americans.

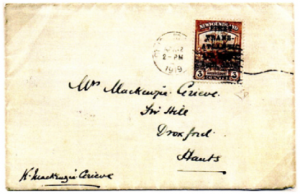

Hawker and Grieve were the first to leave and took off that afternoon. Among the items on board were 95 letters franked with specially overprinted stamps.

Two hundred examples of the current three-cent brown caribou stamp were overprinted “FIRST / TRANS- / ATLANTIC / AIR / POST / APRIL 1919” in six lines. Eighteen of these were defective and destroyed; 95 were used on the mail; and 11 were presented to various officials.

The remaining 76 were purchased by the postmaster general, who then sold them for $25 each to raise money for the Newfoundland Marine Disasters Fund, which supported sailors’ widows and orphans. While there was no suggestion the postmaster made a personal gain from this action, it was a controversial move as some people debated whether money should be raised by the deliberate creation of rare stamps.

Hawker and Grieve’s flight initially went well, but after four hours, the weather deteriorated and their engine began to overheat. The engine was water cooled, and they feared the water would evaporate completely and seize the engine. As the weather continued to worsen, Hawker and Grieve decided to turn south – towards the shipping lanes – and ditched their aircraft beside the Danish ship SS Mary. They were rescued by the Mary, but weather conditions precluded salvaging the aircraft or anything aboard it.

The Mary did not have a radio so could not tell anyone Hawker and Grieve were rescued. After they were missing for several days, it was assumed they were lost, and the King of England sent a telegram of condolence to Hawker’s “widow.”

When the Mary reached land on May 25, six days after rescuing the airmen, and reported Hawker and Grieve were aboard, there were nationwide celebrations.

The Sopwith Atlantic stayed afloat after ditching on May 19 and was found by the SS Lake Charlottesville on May 23. The aircraft was picked up by the ship and later displayed at Selfridges department store in London. The mailbag was handed over to the post office by the ship’s captain.

THE RAYMOR

Raynham and Morgan attempted to take off about an hour after Hawker and Grieve. Although the Martinsyde Raymor was slightly slower than the Sopwith Atlantic, it was considered to be more “efficient” than the Sopwith, and they hoped to overtake Hawker and Grieve somewhere over the Atlantic.

Unfortunately, the Raymor was caught just after take-off by a gust of wind, which blew the aircraft sideways and caused its landing gear to catch the ground. The aircraft crashed, but fortunately, the fuel did not catch fire.

Raynham and Morgan were also carrying a small mailbag estimated at about 30 covers. These covers were all handed in at the post office, and a special stamp with a manuscript overprint was applied. These letters were kept in Newfoundland as Raynham planned to make a second attempt to fly the Atlantic.

Although the crew of the NC-4 hoped to continue their flight across the Atlantic shortly after arriving in Horta, they were stuck in the Azores for 14 days due to waves and the Atlantic swell. This was the same problem that often caused problems for the Pan American Airways flying boats 20 years later.

MAY 27 ARRIVAL

The NC-4 finally arrived in Lisbon on May 27.

The first men to fly the Atlantic were:

- Lieutenant-commander Albert Reed, who was both the navigator and the commanding officer (keeping with U.S. Navy policy at the time);

- Lieutenant Elmer Stone, U.S. Coast Guard pilot;

- Lieutenant Walter Hinton, co-pilot;

- Ensign Herbert Rodd, radio officer;

- Lieutenant James Breese, engineer; and

- Chief Machinist’s Mate Eugene Rhodes, engineer.

The crew of the NC-4 were celebrities.

As they taxied up to the USS Rochester after landing, the cruiser gave them a 21-gun salute, which the Portugese ship Vasco da Gama answered “gun for gun.”

Once onboard the Rochester, the crew of the NC-4 was greeted by the U.S. minister to Portugal, the Portuguese minister for foreign affairs and many more officials. They were also decorated with Portugal’s Order of Tower and Sword.

The final leg of the NC-4’s flight was to Plymouth, England, where they arrived on May 31. The day was declared a city holiday and they were again greeted by numerous officials and a crowd of thousands.

It was initially planned the NC flying boats would carry mail on their flight, but this was changed to reduce the weight of the aircraft; however, two covers carried as favours by members of the crew are known to exist.

One is a letter from Pat Carroll, a Navy machinist on the USS Baltimore, which had supported the NCs when they stopped in Halifax, N.S., en route to Newfoundland. This cover contained a letter dated May 14, 1919, to his brother who was serving in the U.S. Army in France. It was flown as far as Horta, where it was handed over and cancelled on the USS Columbia on May 17th. This cover is now in the collection of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington.

The second is a letter written aboard the USS Columbia and handed to Eugene Rhodes, to be carried to Portugal, where it was supposed to be mailed to Mr. F.J. Weller in Burlington, Iowa, USA. The letter has no cancellations, but there is a note from Rhodes on the back stating that he did carry it on the NC-4, and apologizing for forgetting to mail the letter.

NORTHCLIFFE’S PRIZE

Although the Atlantic was now flown from the U.S. to England, there was still the competition for Lord Northcliffe’s £10,000 prize.

Admiral Mark Kerr arrived in Newfoundland on May 11 with a Handley Page V1500 called “The Atlantic”—like Hawker and Grieve’s aircraft before it. The V1500 was a long-range bombing aircraft ordered with the intention of making night bombing raids on Berlin from airbases in England.

A total of 210 V1500 bombers were ordered in 1918. They were powered by four 350-horsepower Rolls-Royce engines and were designed to carry up to 3,400 kilograms of bombs over 2,100 kilometres and at a top speed of 160 km/h.

The first raid – by three aircraft – was planned for Nov. 8 but cancelled due to engine problems with one of the aircraft. A second raid on Nov. 9 was also cancelled due to engine problems. The aircraft were about to taxi out for the third attempt when news came about the armistice.

The Handley Page Atlantic was modified to carry extra fuel for the Atlantic crossing. It took four weeks to assemble the plane, but when the first flight was made on June 9, it was unsatisfactory.

ALCOCK & BROWN

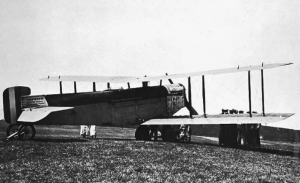

Meanwhile, on May 24, Captain John Alcock, pilot, and Lieutenant Arthur Whitten Brown, navigator, arrived with a modified Vickers Vimy.

The aircraft was a twin-engined bomber powered by two Rolls-Royce 350-horsepower engines. The original Vickers Vimy was designed to carry 1,130 kilograms of bombs over 1,500 kilometres at 160 km/h.

Alcock and Brown’s aircraft was also modified to carry extra fuel for the trans-Atlantic flight.

Although the Vickers Vimy was smaller than the V1500, it was still too large to be assembled inside any of the buildings in St. John’s, so it was assembled in the open.

The Vickers Vimy was assembled quickly and made a trial flight on June 9.

While the Handley Page and Vickers aircraft were being assembled, the Martinsyde Raymor was repaired and ready for a second attempt to fly the Atlantic; however, Major Morgan was injured when the aircraft crashed on its first attempt. He returned to England, and the Martinsyde team was waiting for a replacement navigator to arrive.

Alcock and Brown were the first of the three teams to attempt a trans-Atlantic flight when they took off from Lester’s Field in St. John’s at 1.45 p.m. on the afternoon of June 14.

Many accounts have been written of their harrowing flight, during which they encountered thick fog and dense clouds and were buffeted by the wind and sleet. Their wind-driven electrical generator failed, and they lost radio contact as well as the heating system for their flying suits. Keep in mind the Vickers Vimy had an open cockpit.

I remember reading a dramatic account of their flight in my parents’ Readers Digest when I was a boy. It didn’t immediately turn me into an aerophilatelist, but it did influence my later interest in trans-Atlantic airmail when I became an aerophilatelist.

Alcock and Brown crossed the Irish Coast after flying for 16 hours and landed near Clifden, Ireland.

They wanted to land as soon as possible because they were worried Admiral Kerr may have taken off shortly after they did and might touch down first if they kept flying.

They selected a green field to land on, and as they approached it, they saw several people waving at them. They thought the people were indicating a good place to land, but it turned out they were trying to indicate the “field” was a bad place to land as it was the Derrygilmlagh Bog.

The undercarriage of the Vickers Vimy sank into the bog as the aircraft slowed down, and it came to a stop with its tail in the air. Fortunately, neither Alcock nor Brown were injured.

The pair carried 197 covers on their flight.

Newfoundland’s postmaster general arranged for all the competitors to carry mail, but instead of producing a stamp for each flight, a 15-cent stamp was overprinted “Trans-Atlantic / AIR POST / 1919 / ONE DOLLAR.”

Although Alcock and Brown won Lord Northcliffe’s prize, the Martinsyde team decided to try and beat their time for the Atlantic crossing.

Major Raynham and a new navigator – Lieutenant John Biddlecombe – took off at 3:15 p.m. on July 17. After covering 45 metres, the aircraft plunged downwards and was wrecked. Fortunately, neither Morgan nor Biddlecombe were injured.

Major Raynham returned to England by sea, taking with him the covers from both attempted flights; however, he forgot about the mail until there was an official enquiry. He then remembered the mailbag was stored with his luggage, handed it over and the covers were backstamped by the post office on Jan. 7, 1920.

Admiral Kerr decided to fly to the U.S. rather than attempt a trans-Atlantic flight as the Handley Page company was approached to give demonstration and mail flights. The Atlantic took off from Newfoundland at 6:30 p.m. on July 4 carrying a crew of six, but a serious oil leak forced the plane down near Parrsboro, N.S. The machine sustained considerable damage on landing and did not fly again until Oct. 9.

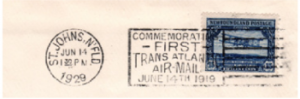

A 15-cent stamp issued in 1928 to commemorate Newfoundland’s history shows the Vickers Vimy taking off. A commemorative postmark was also used to mark the 10th anniversary of their flight.

A LASTING CELEBRATION

Alcock and Brown immediately became celebrities. Their fame has endured over the years, and many commemorative stamps and covers have been produced to commemorate their flight.

In 1928, the 15-cent value in a set of stamps designed to publicize Newfoundland showed the Vickers Vimy taking off.

The following year, special slogan postmarks to commemorate the flight’s 10th anniversary were used in Fredericton, N.B., Hamilton and Toronto.

A commemorative postmark was also used in St. John’s, Nfld., to mark the 10th anniversary of their flight. The postmark was only used for one day – June 14, 1929 – and post office records show more than 24,000 letters and cards were cancelled that day. The total sale of stamps on June 14 was $4,000 higher than normal.

Since then, covers – and sometimes stamps – have been produced on the 14th, 50th, 60th, 75th and 83rd anniversaries of Alcock and Brown’s flight (and possibly on other dates, too).

Canada Post is slated to issue a set of stamps celebrating Canadian aviation on March 26, and Ireland’s An Post will also issue stamps for the flight’s 100th anniversary.

In contrast, the fame of the crew of the NC-4 rapidly waned. They met U.S. President Woodrow Wilson on June 4 in Paris, where he was attending the Paris Peace Conference, but by the time they returned to the U.S. at the end of June, attention and acclaim shifted to Alcock and Brown for their non-stop trans-Atlantic flight.

Very few covers have been produced to commemorate the flight of the NC-4, but a number can be found commemorating talks by Walter Hinton.

During the 1920s, Hinton was involved in a number of aeronautical adventures, including exploring the Arctic by balloon and the Amazon rainforest by hydroplane. He then founded the American Aviation Institute, published several periodicals on aviation and spent years touring as a speaker promoting aviation.

Chris Hargreaves is the editor of The Canadian Aerophilatelist, the quarterly journal of the Canadian Aerophilatelic Society, of which he’s also a past president. This story appeared in the March 2019 issue (#118) of The Canadian Aerophilatelist.