By Jesse Robitaille – Editorial originally published in CSN Vol. 43 #23

He’s somewhat deified for his seminal, incomparable role in forming modern Canada, but he’s also increasingly vilified for propping up the country’s damaging Indigenous policy.

Canada’s first prime minister won his last election on March 5 – the issue date for this edition of CSN – nearly 130 years ago.

John A. Macdonald was the leader of the former Conservative Party of Canada, which was established along with Confederation in 1867 (before being reinvented as the Progressive Conservative Party in 1942; six decades later, it merged with the Canadian Alliance to form the present-day Conservative Party).

Challenging first-time Liberal leader Wilfrid Laurier in the 1891 general election – Canada’s seventh – Macdonald earned 121 seats and 51.5 per cent of the popular vote.

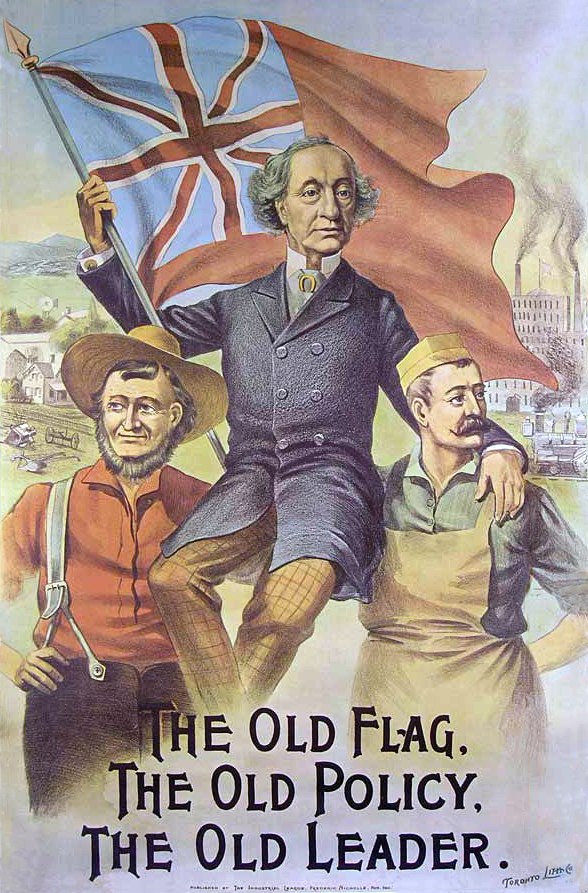

It was the fourth consecutive majority for the 76-year-old Macdonald, who campaigned under the slogan, “The old man, the old flag, the old policy.”

At the time, this traditional, tried-and-true messaging worked well for the architect of Confederation—a lawyer with a well-established proclivity for alcohol and who had already survived a major bribery scandal.

MACDONALD IN MODERN LIGHT

Today, that message – one that calls back to Macdonald’s mission of uniting the country by “Clearing the Plains” – is lampooned by people who are charged with rewriting history for suggesting his legacy be reworked.

Governments across the country have discussed removing Macdonald’s name from public buildings and tearing down statues erected in his honour.

Last year, the City of Victoria in British Columbia spent $30,000 to remove one statue as a symbol of reconciliation with Canada’s Indigenous communities.

Supporters of the teardown cite Macdonald’s role in establishing the residential school system, which forcefully removed 150,000 First Nation, Inuit and Métis children away from their communities and families—something that still reverberates through society today.

Indeed, the 19th century was an entirely different time and place than the present day, and people who are fearful of “rewriting history” also suggest modern society has no place in judging its forefathers on today’s moral footing.

But while other Macdonald statues, these challenged by the court of public opinion, are being defaced, Macdonald’s legacy lives on in other ways.

MACDONALD STAMPS

As recently as 2017, Macdonald was featured on a Permanent stamp in the fifth and final set of the Canadian Photography series.

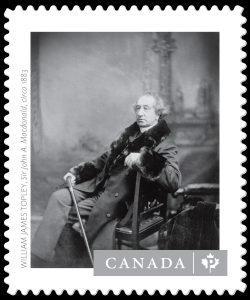

More recently, Canada’s first prime minister was commemorated on another Permanent stamp featuring William James Topley’s 1883 photograph of Macdonald.

Two years earlier, on the 200th anniversary of his birthday, he was celebrated with on another stamp.

Decades earlier, in 1973, Macdonald graced a one-cent definitive.

He was also previously honoured on a one-cent stamp in 1927 to mark the 60th anniversary of Confederation.

In 1927, a two-cent stamp featuring Robert Harris’ 1883 painting Fathers of Confederation also depicted Macdonald. The same design was used on a three-cent stamp issued in 1917 to mark Confederation’s 50th anniversary.

Against the backdrop of torn down and defaced statues, how will these stamps fare in the audit of Macdonald’s historical legacy?