By Jesse Robitaille

This is the first story in a three-part series highlighting Great Britain’s mid-19th century postal reforms.

Great Britain’s postal reforms in the second half of the 1830s – just before the beginning of the postage stamp era – allowed communication to flourish while transforming the empire into a mobile society.

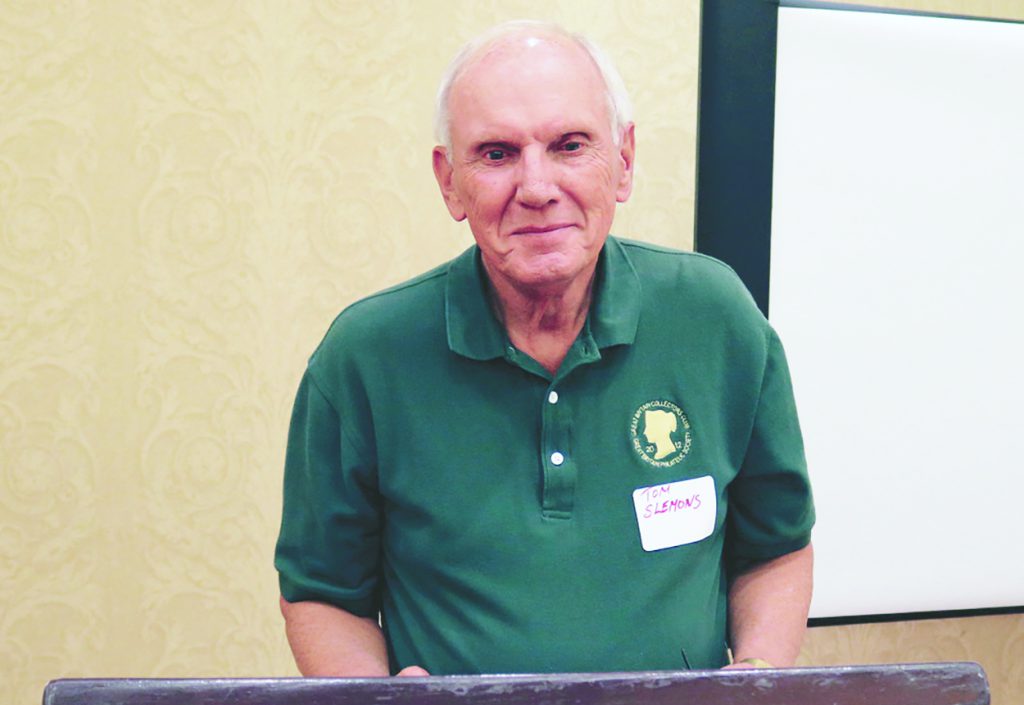

These reforms were the subject of a June 22 presentation by Tom Slemons, a U.S.-based director of the Great Britain Collectors Club and a Fellow of the Royal Philatelic Society London.

“This is why you can mail a letter from one end of Canada to the other at a single rate, or from one end of the U.S. to the other for 50 cents,” said Slemons, who explored the inefficiencies of the pre-reform mail system at this summer’s convention of The Royal Philatelic Society of Canada.

“If you hadn’t had postal reform, you couldn’t do that.”

While the old system lacked fiscal control and required an unwieldy workforce, the reforms conceptualized by Rowland Hill realized their full capabilities when the uniform penny post was introduced in 1840, less than six months before the world’s first postage stamps were issued.

There are “many misconceptions” about why the reforms were initiated by the British government, Slemons said.

“Its sole objective was not to get cheap postage; that was one of its objectives, but Rowland Hill was an outsider and looked at the operation of the British post office at the time, and it was basically horrible. There were some good parts about it, but there were also terrible parts about it.”

It was possible to mail a letter from London one day, for example, and receive a response the following day.

“You can’t do that today,” said Slemons. “That part of it was phenomenal, but the inefficiency of the post office was horrible.”

PRE-REFORM PROBLEMS

Part of the post office’s inefficiency was owed to its cumbersome workforce, which saw entire divisions dedicated to superfluous tasks.

“When a postmaster out in the countryside posted a letter, he knew the rate to London as well as additional charges to the suburbs of London. If it was going to go someplace beyond London, they had a division in the post office where all these letters would be handled, and the rate on the letter would be changed to the new rate on delivery to the final addressee.”

Aside from processing, the logistics of mail delivery were also burdensome for the post office.

“You could send a letter either paid or unpaid – your choice – and there was no difference in charge. If it was an unpaid letter, the postman had to collect it from the addressee, but if the addressee wasn’t home, then he had to come back and do it again the next day. And what if they didn’t happen to have that amount of money on hand? It was very inefficient from that standpoint.”

The pre-reform system also required a dangerous level of trust due to its lack of tracking, Slemons said.

“Let’s say the postmaster just reported his income; you had no knowledge of whether or not he was telling the truth or if he was getting any additional funds on the side for one thing or another.”

Beyond the postmaster, there was also widespread fraud on the part of consumers.

“People did everything they possibly could to cheat the post office,” Slemons said. “They charged based on distance, weight and sheets of paper, so you’d see a letter that said single sheet, but if they could slip a second sheet inside, they would get a double-rate letter at half the price.”

To combat this type of fraud, the post office used a technique known as “candling,” which saw employees hold mail in front of a light to see if there was a second sheet of paper hidden within.

“It was ridiculous.”

The widespread abuse of free franks – a type of hand-stamp applied to mail to indicate it required no postage – also created monumental losses for the post office.

“With free franks, members of parliament, other government officials and church officials had the ability to send a letter at no charge. The post office was very specific about the rules on how you had to do it, but it was abused.”

By the 1830s, about five million free franks were used annually, according to Howard Robinson’s 1948 book The British Post Office: A History.

“Hill looked at the capability of the system to deliver the mail and how it could be done more efficiently,” said Slemons, who added the reforms also focused on fiscal control, staff reduction and faster mail delivery.

POST OFFICE REFORM

In 1837, Hill published a pamphlet – Post Office Reform: Its Importance and Practicability – to express his views.

“It occurs in a number of versions, so if you happen to be a collector of philatelic literature, it’s quite a challenge to get all the copies that are available.”

The Mercantile Committee, of which Hill was a member, was formed to determine the plausibility of changing the mail system, including its postal rates.

“An off-shoot from that was the Select Committee, which later on did a lot of examination of the fiscal side of things as well as the capability to handle more mail,” said Slemons.

“The cost of postage was very high. It was outrageous, in fact, and was raised to its highest level starting in 1812 to finance the wars that were going on. Postage was a tax. It had nothing to do with the cost of transporting a letter from A to B. Businessmen wanted cheaper postage to advertise, and the public wanted it.”

At this time in the mid-to-late 1830s, Britain was “not a very mobile society,” Slemons said.

“You were kind of stuck wherever you were, but with cheaper postage and the capability to communicate, Britain would become a much more mobile society.”

Despite the societal benefits of cheaper postage, the post office was concerned about continuing to make a profit amid these reforms.

“They were making a profit at the exorbitant rates, but there was also concern about the capability of the postal system to handle an increased volume of mail if they lowered the postage rates. They weren’t sure if they could do that.”