On today’s date in 2011, the Supreme Court of Canada unanimously sided with the Public Service Alliance of Canada (PSAC) in a 28-year-old, $150 million pay-equity dispute with Canada Post.

The decision, which was delivered by Chief Justice Beverley McLachlin, reinstated a $150 million award for employees of Canada Post. The dispute dated back to 1983, when PSAC filed a complaint on behalf of about 2,300 employees, most of them women.

The complaint claimed Canada Post “paid lower wages to clerical workers compared to work of equal value performed by men in various operations jobs, including letter carriers,” according to a 2011 National Post story.

The case was resolved on Nov. 17, 2011, as McLachlin upheld a Canadian Human Rights Tribunal decision, which discovered a wage gap for women working in clerical jobs and awarded them $150 million in 2005.

“We are thrilled,” said Patty Ducharme, then PSAC’s executive vice-president, in 2011. “This is the end of the line. It is so wonderful that finally, after 28 years, we will be able to say to people, ‘It’s over, we have a decision and it’s over.'”

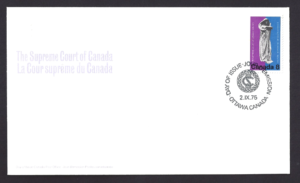

A first-day cover released as part of the Post Office Department’s 1975 Supreme Court issue is cancelled in Ottawa, Ont.

1975 SUPREME COURT STAMP

On Sept. 2, 1975, Canada’s Post Office Department (known as Canada Post since 1981) issued an eight-cent stamp to mark the centenary of the Supreme Court of Canada.

When the stamp was issued, the court held three 11-week sessions each year; today, the court sits for 18 weeks of the year, beginning on the first Monday of October and running until the end of June or July.

“By law, three judges come from Quebec and custom appears settled that three will come from Ontario, one from the Atlantic Provinces and two from the West,” reads a press release issued by the Post Office Department in 1975.

“The Supreme Court, Canada’s court of last resort, is a general court of appeal for both criminal and civil cases. Questions concerning the British North America Act, the constitutionality or interpretation of federal or provincial legislation, the powers of governments and other matters, may also be referred to the tribunal for consideration. The Supreme Court thus expresses a national jurisprudence and is an expositor of ‘the national legal conscience.’

“The Fathers of Confederation believed that Canada would require a unifying legal force, an independent authority to adjudicate whenever disputes occurred over the division of powers in the new federation. Consequently, the British North America Act gave parliament the power to provide for ‘the constitution, maintenance and organization of a General Court of Appeal.’ The government of Sir John A. Macdonald introduced two bills for the establishment of such an institution but withdrew them because of ‘The difficulties connected with… establishing a court satisfactory to the Province of Quebec.’

“In 1875 Télesphore Fournier, Minister of Justice in the government of Sir Alexander Mackenzie, produced a new Supreme Court bill based upon Macdonald’s extensive work. To ensure sound interpretation of the French civil law in Quebec, the bill was amended so that two of the six judges would come from that province. The bill was also amended to prevent appeals from the Supreme Court to British courts except in instances where Her Majesty exercised her royal prerogative. The British were dubious about the amendment and Macdonald objected that it ‘was the first step toward the severance of the Dominion from the mother country.’ Nevertheless the bill and the amendment passed. The Court’s first few years were troubled. In 1879 and 1880, some M.P’s attempted to abolish it. Complaints arose about individual decisions, about delays, about costs to taxpayers and litigants, and about the possibility of damage to provincial rights. Dissent existed among the judges themselves. Two accused one of their colleagues of delivering ‘long, windy, incoherent masses of verbiage, interspersed with ungrammatical expressions, slang and the veriest legal platitudes inappropriately applied.’ Nevertheless, there was general agreement that the institution should survive. Macdonald stated that ‘I have no doubt that, as the Court grows older, the people of the country will become more accustomed to consider it as one of the tribunals of which they should be proud, and of which they would not willingly be deprived.’ Confidence soon increased. The highly qualified people appointed to the Court’s independence and security rose to the challenge with integrity and intelligence. In 1949, with near unanimous agreement, parliament stopped appeals from going over the tribunal to the British. The Supreme Court had at last become supreme in every sense. Allan Fleming of Toronto designed the Supreme Court stamp. He used a photograph of a statue known as ‘Justice-Justitia.’ In 1970 this was erected in front of the Court building along with another statue named ‘Truth-Veritas.’ Walter S. Allward executed both as part of a commission to create a memorial to King Edward VII. The commission was awarded prior to World War I and when the war intervened only two bronze figures were complete. Allward, who was one of the leading sculptors of the period, also designed the Vimy Memorial.”