On today’s date in 1930, hockey legend Miles Gilbert Horton was born in Cochrane, Ont.

Better known to his relatives, friends and future fans as Tim – a name his mother preferred – the future Hall of Famer and restauranteur was the first child of Ethel and Aaron Horton. While his mother chose the name Tim before he was even born, she was too sick to attend his christening, according to Horton’s widow Lori and godson Tim Griggs, who wrote the 1997 book, In Loving Memory: A Tribute to Tim Horton. Instead, his father decided to name the young boy after his two grandfathers, Miles and Gilbert, although those names were rarely used.

“Cochrane sits on the edge of Commando Lake, which really appears to be two lakes, surrounded by parkland and some lovely places to walk. The lake freezes in the winter and Tim used to live just up the street. He used to walk down to the lake with his friends and like a lot of Canadian boys they’d clear a spot and play hockey,” wrote Griggs and Lori Horton.

“People over the years have wondered why so many great NHL (National Hockey League) players have come from these small, Northern Ontario towns. It certainly has a lot to do with long, cold winters and an abundance of frozen lakes and rivers. Ice time is never a problem in a town like Cochrane.”

Growing up in the northeastern Ontario town of roughly 5,500 people, Horton learned to sake by age three before launching into his minor-hockey career in Duparquet, Qué., about 150 kilometres east of Cochrane. He continued honing his hockey skills before moving to Sudbury with his family at age 15, by which time he began developing the dominant physical strength he would later use as one of the NHL’s strongest players.

After playing for the Sudbury High School junior hockey team in 1946, Horton’s friend saw a newspaper ad promoting the tryouts for the local Junior A team, the Copper Cliff Jr. Redmen of the Northern Ontario Hockey Association. For the 1946-47 season, his first in the “Nickel City,” Horton suited up for Redmen; however, in the last game of the finals, he fell into the boards during the second period and left the game with a broken ankle.

In the summer of 1947, Horton helped build the Sudbury General Hospital, which opened three years later, by carrying the building’s bricks up a ladder.

BOUNCING BACK

After Horton’s injury healed, he worked through the summer on the construction of the Sudbury General Hospital.

Much like his on-ice role, his job centred on his strength: Horton was responsible for carrying bricks up a ladder to help build the hospital, which opened its doors in 1950 before closing in 2010.

“By the end of the summer, he was back in excellent physical condition,” wrote Griggs and Lori Horton.

That fall, Horton was scouted and signed by the Toronto Maple Leafs, and he received a sports scholarship with St. Michael’s College, whose team – the Majors – played in the Ontario Hockey Association (OHA).

A 1949 St. Michael’s College yearbook illustration showcases Horton as ‘a star on the Majors defense for two seasons.’

“In his first season, Horton racked up the most penalty minutes in the OHA with 137,” Mike Commito and Lorraine Snyder wrote for the Canadian Encyclopedia, adding Horton had already earned a “reputation as a strong defenseman but also demonstrated that he could skate and score like a forward.”

He netted six goals and seven assists that season, and while he was placed on the Leafs’ reserve list, Horton was left to develop for another season in the OHA—a wise move given how he would perform in his sophomore effort.

“The following season, he continued to hone his reputation as a tough defender, but also demonstrated his finer skills, earning top honours in the OHA as the league’s best defenseman,” Commito and Snyder wrote.

The earliest known signed photograph of Horton shows him in his first season with the Pittsburgh Hornets. Sold at a Texas auction in 2010, the photo brought $776.75 US. Photo by Heritage Auctions.

FIRST PRO CONTRACT

Coming off a nine-goal, 18-assist season in 1948-49, Horton attended the Leafs’ training camp in St. Catharines, Ont.

At the camp, he impressed his coaches enough to earn his first professional contract with the organization’s farm team, the Pittsburgh Hornets of the American Hockey League. He was paid $9,000 across his three-year contract plus a $3,500 signing bonus, according to In Loving Memory.

“As soon as his cheque cleared, Tim went out and bought himself his first car, a 1949 Mercury,” Griggs and Lori Horton wrote.

In 1949-50, Horton’s first season with the Hornets, he managed five goals and 18 assists as the team fell short of making the playoffs.

The next season, Horton put up eight goals and 26 assists before the Hornets made the playoffs, falling to the Cleveland Barons in the finals.

In his final year with the Hornets, Horton helped his team to a league-best 46 wins with 12 goals and 19 assists. During the team’s run for the Calder Cup, he bolstered the blue line to lead the Hornets to their first championship.

Coming off his Calder Cup victory, Horton laced up full time with the Leafs in the 1952-53 season, marking “the start of what would be a long career as a stalwart on Toronto’s blue line,” Commito and Snyder wrote.

Horton would play in 24 National Hockey League (NHL) seasons for the Leafs (1949-70), the New York Rangers (1970-71), the Pittsburgh Penguins (1971-72) and the Buffalo Sabres (1972-74).

In that time, he won four Stanley Cups, including one in 1967—Toronto’s last championship. Overall, he played “an integral part of four Stanley Cup-winning teams, including three consecutive victories from 1962 to 1964,” Commito and Snyder added.

“While Tim Horton’s most enduring popular legacy is his coffee and donut franchise, he has also been both remembered and recognized for his contribution to the Toronto Maple Leafs during his nearly 20-year tenure with the team. He continues to be remembered as one of the strongest players of the game. In 1,446 regular-season NHL games, Horton scored 115 goals, made 403 assists and racked up 1,611 penalty minutes.”

After Horton was traded to the Rangers in March 1970 – closing the curtain on a 1,185-game sting with the Leafs – the Penguins claimed him in an intra-league draft. A year later, he was picked up in another intra-league draft by a relatively new franchise, the Buffalo Sabres, who made their NHL debut in 1970.

“At the time, the Sabres’ coach and general manager was Punch Imlach, Horton’s coach during his glory days with the Leafs,” wrote Commito and Snyder. “Imlach knew Horton well and valued the skill and experience he would bring to the upstart franchise in Buffalo.”

HORTON’S BUSINESSES

Despite his elite status on the ice, Horton was paid a paltry salary – typical for the time – and never took home more than $20,000 a year (and sometimes as low as $3,000 a year).

But it was Horton’s “entrepreneurial spirit,” as Commito and Snyder wrote, that pushed him down a business path.

In the early 1960s in North Bay, Ont., he first launched a hamburger restaurant under the soon-to-be-famous Tim Horton name. He also owned a Studebaker dealership, Tim Horton Motors, in Toronto about two years before opening his first Tim Horton Doughnut Shop in nearby Hamilton in 1964.

Canada’s largest quick-service restaurant chain, Tim Hortons (as the company is now known) has about 4,800 restaurants in 14 countries.

In 2014, Burger King purchased Tim Hortons for $11.4 billion US, and a few months later, the chain became a subsidiary of the holding company Restaurant Brands International, which is majority owned by the Brazilian investment firm 3G Capital.

UNTIMELY DEATH

On Feb. 20, 1974, Horton – then 44 and the second oldest player in the NHL – suited up for his 124th game with the Buffalo Sabres.

Playing against his former team, the Leafs, Horton was named one of the game’s three stars despite managing just one shot and receiving a tripping penalty.

The Sabres lost 4-2, pushing the team below a .500 win percentage with a losing record of 26-25-6.

With his coach’s permission to drive back to Buffalo after visiting his family in Toronto, Horton made his way out of the Ontario capital in the early hours of the morning on Feb. 21.

Horton (bottom left) is one of six NHLers commemorated in the 2002 ‘NHL All-Stars’ issue. The series ran from 2000-05.

Seen travelling at high speeds at about 4 a.m. in Burlington, Ont., Horton approached the Lake Street exit in nearby St. Catharines when he lost control of his Ford Pantera, according to Griggs and Lori Horton. He was found nearly 40 metres from his totalled car, which rolled several times before coming to a stop in the opposite lane.

“When Horton’s speeding Pantera sports car went off the QEW in St. Catharines, Ont., rolled on the median and flung Horton out the passenger door, his own life had accelerated to a precarious velocity,” wrote Douglas Hunter in his 2012 book, Double Double: How Tim Hortons Became a Canadian Way of Life, One Cup at a Time.

“His wife, Lori, was battling alcohol and prescription pills, and according to Ron Joyce’s memoir, Horton had an apartment in Oakville, Ont., near the restaurant company’s head office, where he was carrying on an affair. Horton himself had begun drinking again — his blood-alcohol level at the time of his death was more than twice the legal limit — and traces of barbiturate in his bloodstream and pills in his pocket indicated he had been taking the same highly addictive diet pills, Dexamyl, as Lori. He also had amphetamines in his pocket, which suggested that he had been using uppers to get through the grind of the NHL season at age 44.”

On his way through southern Ontario, Horton stopped in Oakville for an impromptu meeting with Joyce, his business partner.

“Horton had knocked back vodka and soda while they hashed out issues; a vodka bottle, its neck broken off, was found on the median at the crash site,” Hunter wrote. “The conversation, according to Joyce, was testy at times, but they had parted amicably, with Horton declaring, ‘I love ya, Blub’ – a nickname that poked fun at Joyce’s waistline — and planting a kiss on his cheek before getting behind the wheel of his Pantera and speeding into oblivion – and a peculiar mix of posthumous fame and infamy.”

Horton’s autopsy was only made public in 2005, more than three decades after his death.

Horton and teammate Allan Stanley pose beside the Stanley Cup in 1964 after the Leafs won the team’s third consecutive championship.

RESPONSE FROM THE HOCKEY COMMUNITY

Horton’s early morning death was met with “shock and despair,” according to an Associated Press report published one day after Horton’s death.

“I was shocked to hear of Tim’s untimely death,” Imlach told the Associated Press. “I’ve been associated with him on many Stanley Cup championship teams, and he was the backbone of our team in Buffalo. He was not only an all-star defenseman, but he was a great person, too.”

After hearing of Horton’s death, Leafs President Harold Ballard ordered the lowering of all flags at Maple Leaf Gardens.

“I’ve lost a great friend and hockey’s lost a great competitor,” Ballard told the Associated Press.

Other tributes focused on Horton’s “quiet strength, dedication and the fact he was a gentleman,” according to a Montréal Gazette report published the day he died.

“Horton was a tremendous competitor, a great person,” Montréal Canadiens manager Sam Pollock was quoted as saying in the Gazette report. “Nothing was too much, no task too great. There were no ifs, ands or buts. He did the job, injured or not.”

Known for his on-ice tenacity, Horton was “the strongest skating defenseman in hockey,” Pollock said, adding the future Hall of Famer “used his strength legally.”

“He was never vicious.”

His close friend Ron Schock, the Penguins’ captain, told the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette Horton “was the kind of man you look to for leadership.”

“I never heard anybody say a bad word about him.”

Dave Burrows, another teammate during Horton’s one-season stint with the Penguins, added: “He was a real inspiration to me. I learned from him both by his example and by the things he said. It’s a shame—he was ready to go out and enjoy all of the pleasures he missed as a hockey player, and now this.”

After Horton’s death, Joyce purchased the Horton family’s shares in the doughnut business, which then had 40 stores, for $1 million.

Some of Horton’s many NHL achievements include:

- being named a First Team All-Star in 1964, 1968 and 1969;

- being named a Second Team All-Star in 1954, 1963 and 1967;

- being posthumously inducted into the Hockey Hall of Fame in 1977;

- being posthumously inducted into the Buffalo Sabres Hall of Fame in 1982;

- having his #2 jersey retired by the Buffalo Sabres in 1996;

- ranking #43 on The Hockey News’ list of the “100 Greatest Hockey Players” in 1998;

- ranking #59 on the CBC’s “Greatest Canadian” list in 2004;

- receiving the Bruce Prentice Legacy Award by the Ontario Sports Hall of Fame in 2015;

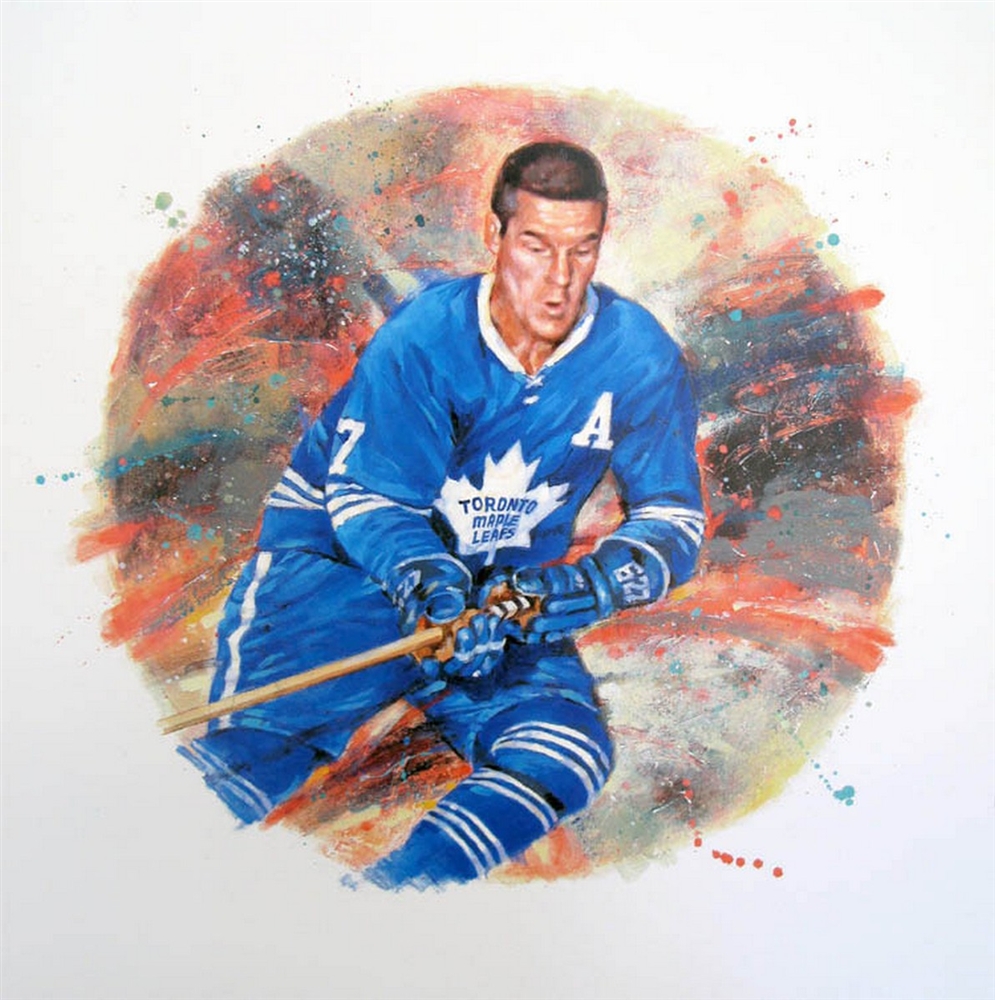

- having his #7 jersey retired by the Toronto Maple Leafs in 2016; and

- being named one of the “100 Greatest NHL Players in history” by the league in 2017.